How We Build Flood

Written for Flood.io

Introduction

19 years after the Agile Manifesto was published, there aren’t many development teams left that aren’t using some variation of the Agile methodology to create software, and for good reason. Its emphasis on continuous, iterative, and cross-functional delivery enables teams to ship meaningful, high-quality code more often, adapting to modern timeframes.

For a while, the Flood team operated under Scrum, but we soon began to see some issues with our implementation of the methodology.

- The tight, two-week sprints and endless backlog began to feel repetitive and futile. It sometimes felt like we were stuck in the cycle of maintenance, unable to truly innovate.

- Scrum’s strict processes sometimes felt unnecessary in our small, casual team of less than 10 people.

- Features weren’t being shipped as quickly as we wanted.

So we went back to the drawing board, and thought about times when felt the most productive. Some of us mentioned GIG, the annual Tricentis-wide three-day hackathon where the Flood team would split up into three or four groups to work on something new (read more about Flood’s participation in this year’s GIG here). What made it different from Scrum’s sprints? We decided to try to recapture that hackathon excitement in our daily work.

This led us to a methodology called Shape Up.

What is Shape Up?

Shape Up is a methodology for creating and maintaining software within a cross-functional team. Shape Up treats a piece of work as a raw idea that needs to be shaped, pitched, bet on, and then built by the development team. It was created by Basecamp, and you can learn more about it in their excellent book here.

We consider Shape Up to be a type of Agile methodology, although this hasn’t been officially confirmed.

A Shape Up project has four stages:

- Shaping

- Pitching

- Betting

- Building

Shaping

Shaping work involves taking something from a raw idea and turning it into an actionable project that is ready to be pitched. In general, a small group of managers or senior staff shape work for the rest of the team. However, this was our first major deviation from canonical Shape Up. While our co-founder, Tim Koopmans, did the initial round of shaping for our first Shape Up project, the rest of the team quickly took the reins after that. In our small team, everyone is considered a “senior staff” member, so everyone is welcome to shape and pitch work they find interesting.

Shaping work involves going through the following steps:

1. Set boundaries

First, the project is bounded and limited to something that fits the time period. Scope is determined based on the appetite.

An appetite is completely different from an estimate. Estimates start with a design and end with a number. Appetites start with a number and end with a design. We use the appetite as a creative constraint on the design process. - Basecamp

2. Create a prototype or proof of concept

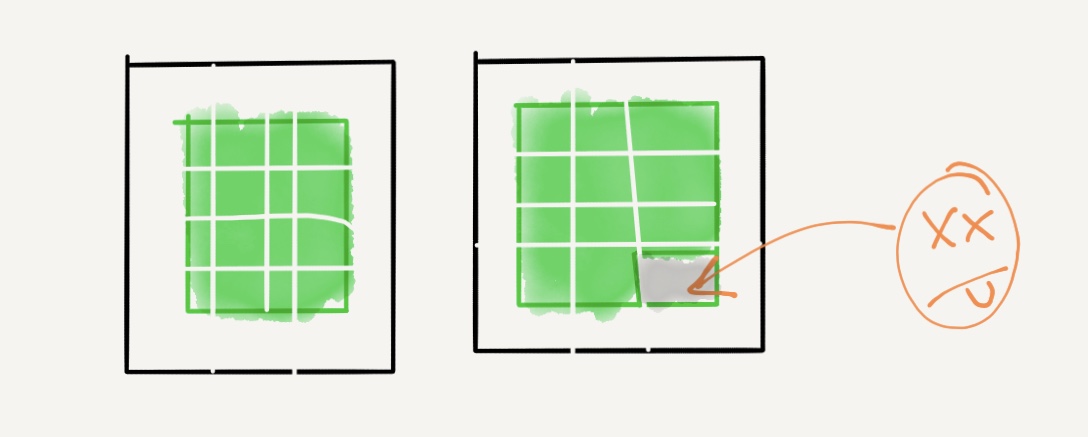

Next, a rudimentary design is created that briefly describes how the new feature would work. This could be a very rough mock-up of UI or just handwritten text to represent menus. “Rough” is key here: the design should be far from polished, because some work may not even proceed past the shaping phase.

Here’s an example of a mock-up that our Principal Engineer, Lachie Cox, used to illustrate an idea during the shaping phase.

3. Reduce scope, address risks and rabbit holes

The last part of shaping a piece of work is making it as simple as possible by descoping anything unnecessary and addressing any foreseeable risks that might come up.

In the traditional Shape Up methodology described by Basecamp, shaping is done by a separate, managerial team that works in parallel with the development team. This didn’t really fit with our smaller, mostly flat team, so we changed it. At Flood, anyone can shape.

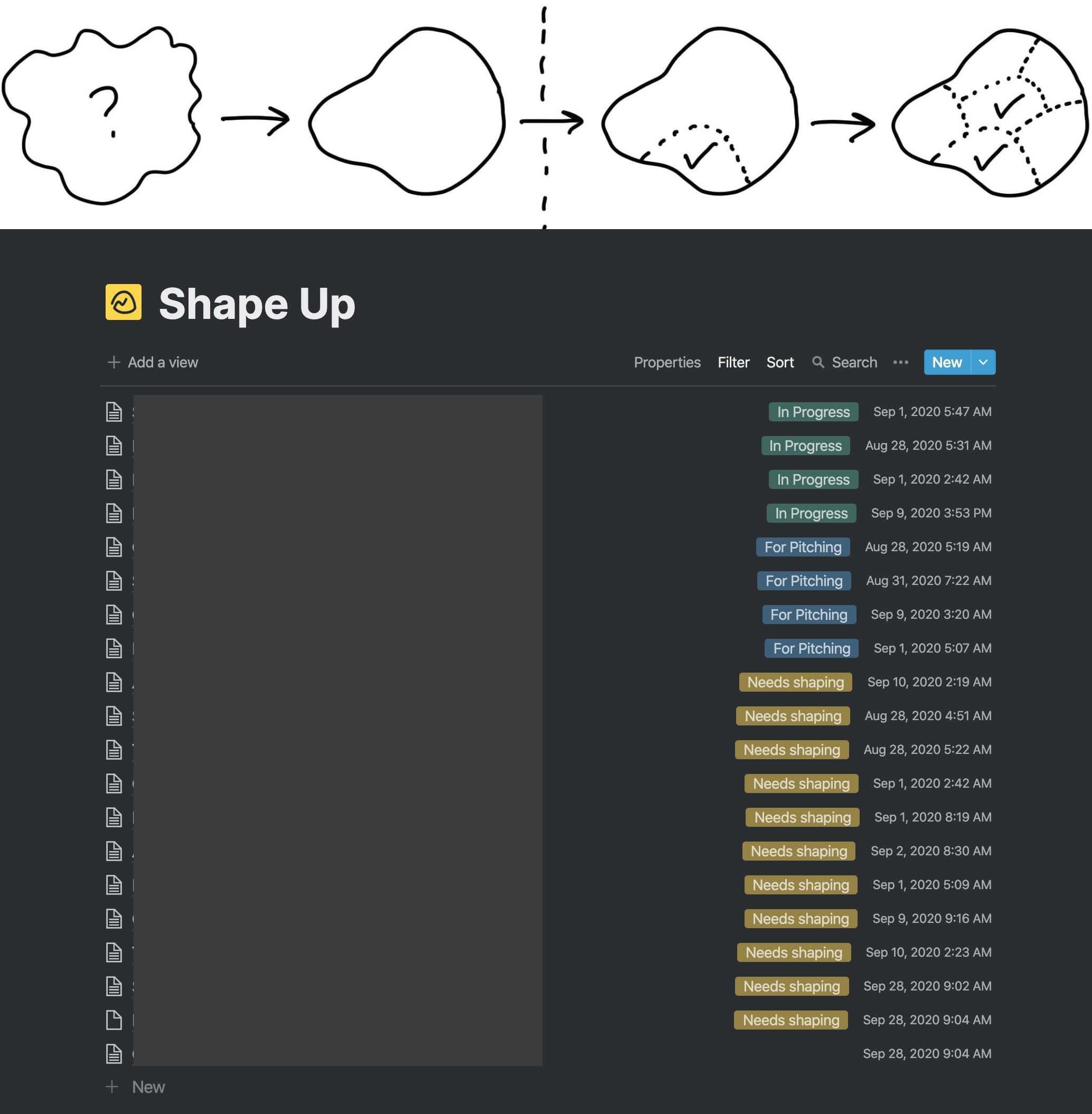

We keep a running list in Notion of work in different stages of the process. Anyone can create an idea or pick up an idea proposed by someone else, and put work into shaping it. Here’s what that looks like:

Pitching

The pitch is a proposal including concise and high-level statement of the problem, solution, design, and implementation of a piece of shaped work. After pitches are made, management staff goes to the betting table.

Again, we removed the restriction of pitching to management staff and opened it up to anyone on the team who feels strongly enough about a piece of work to put a pitch together.

A pitch includes the following components:

- Problem - The raw idea or use case

- Appetite — How much time we want to spend and how that constrains the solution

- Solution — The core elements we came up with, presented in a form that’s easy for people to immediately understand

- Rabbit holes — Details about the solution worth calling out to avoid problems

- No-gos — Anything specifically excluded from the concept: functionality or use cases we intentionally aren’t covering to fit the appetite or make the problem tractable

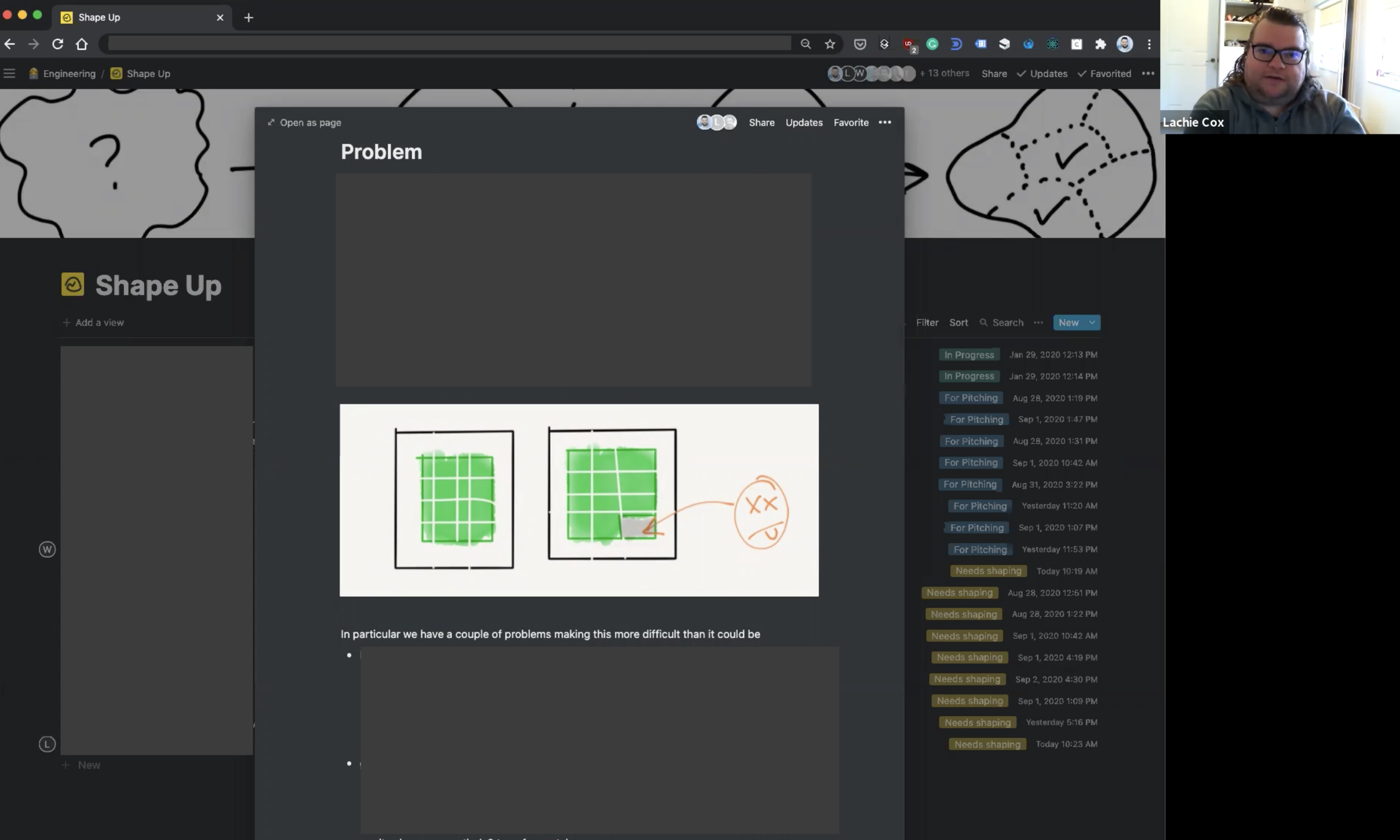

The actual pitching can be done asynchronously by posting it somewhere for people to review in their own time, but it can also be done in a meeting. We prefer to go through all the pitches in a Zoom call with the Flood core team. Here’s Lachie pitching a project:

The pitching call is a great way to get the team together to see what we could be working on in the future. It’s usually an exciting time, because it’s often the first time we get a glimpse of some cool ideas that could be coming Flood’s way.

Betting

After the pitching call, we usually have a day or two to further discuss the pitches, raise objections, think of anything else that might not have been addressed. Then, we have a betting call.

In the betting phase, we go to the “betting table” to discuss which bets, or projects, we want to place for the next cycle. We ask each other questions like:

- “Does the problem matter?”

- “Is the appetite right? - Do we want to bet six weeks on this?”

- “Is the solution attractive?”

- “Is this the right time?”

- “Are the right people available?”

At the end of the call, we decide, as a team, which combination of the pitches we want to move forward with.

Building

Once the bets are placed, we wait until the current Shape Up finishes and then begin the new cycle. A kick-off meeting between the members of the selected team for each piece of work is usually held, where details of the pitch are rehashed or expanded upon.

Once the cycle has started, teams are given space to do uninterrupted work. Uninterrupted work means that members of the team are not assigned new work that is unrelated to the Shape Up project. This courtesy lets them put their full concentration towards building the project, doing Deep Work to maintain momentum and productivity.

Once bets are committed to and teams are chosen, we honor it. We don’t pull team members away on other tasks. We don’t let them get distracted. We leave them alone and get them to fully engage in the shaped work. - Jason Fried, Basecamp.

Initially, teams may have a sort of radio silence as each team member determines where to start first and collects their thoughts on the shaped pitch. Allow up to three days.

Teams work to deliver a scope including front-end and back-end functionality that can be demoed at the end of the first week. A scope is a piece of demo-able work that might not have all the functionality of the finished product, but does have both back-end and front-end elements integrated, albeit small slices of each.

Instead they should aim to make something tangible and demoable early—in the first week or so. That requires integrating vertically on one small piece of the project instead of chipping away at the horizontal layers. - Jason Fried, Basecamp

Building work in integrated “slices” like this increases the likelihood of any showstopping issues coming up earlier during the cycle, rather than towards the end. As more and more of the work is known, teams make a “scope map” of all scopes that will need to be realized before the work can be considered built.

Basecamp talks about the use of “hill charts” to show progress, but so far we have tended to just discuss project updates during one of our regular team meetings. Hill charts are interesting, though, and we might consider trying them out in the future.

Testing and QA need to happen within the cycle, but documentation and marketing do not.

Weaknesses of Shape Up

No structure around non-production cycles

Shape Up emphasizes being in production mode, where work is actually built, but being constantly in a state of production is not realistic. In fact, Shape Up acknowledges this by introducing several non-production modes such as R&D mode, bug smashes, or the cool-down. The existence of these modes calls Shape Up’s long-term sustainability into question and opens up the possibility of staying longer in non-production modes than in the production mode.

Since there is no structure to when production cycles should be interspersed with non-production cycles, it can be difficult to maintain the balance between getting stuff built and fixing bugs. We’ve experienced both extremes: sometimes we move a little too fast on the building and let defects slip through, and sometimes we get too caught up in fixing defects and fall off the Shape Up cycle wagon.

Reliance on a separate management staff may not be great for smaller teams

Despite the fact that Shape Up emphasizes the development team’s freedom to implement solutions, all work is canonically still shaped, pitched, and bet upon by management. It’s too easy for managers to shape work to the extent that development teams no longer have meaningful decisions to make, and the work becomes a matter of filling in the blanks.

We’ve addressed this issue by opening up all phases to anyone on the Flood team.

The principle of uninterrupted work during the building stage is unrealistic.

While the team is in the Building stage, they are meant to be allowed to work solely on the project. While deep work is essential for productivity, it’s difficult to imagine having all the teams unreachable for the length of the cycle, which in Shape Up is longer than normal at six weeks.

A possible solution would be to have staggered cycles that still leave some people around to react to issues that come up while freeing up others to go into production mode.

Shape Up cycles include testing, but not documentation and marketing activities that are also essential.

In smaller teams, Shape Up does not include non-developer members. This could be addressed by making documentation/marketing an essential component of a cycle and by allowing non-development projects to be pitched.

Shape Up doesn’t explicitly include time for reflection or retrospection, although presumably this could be done in the cool-down period.

Our success with Shape Up

We’ve been using the Shape Up methodology for a year, since September 2019. So far, our experience has been generally positive. It addresses all of the issues we had with Scrum:

The tight, two-week sprints and endless backlog began to feel repetitive and futile. It sometimes felt like we were stuck in the cycle of maintenance, unable to truly innovate.

Shape Up lets us come up with some cool ideas that we’re actually excited to work on, which is far from having a laundry list of bugs to fix. It’s also inspired some innovation and blue-sky thinking in the team, which is empowering.

The six-week cycle was also less stressful for us because it gave us a chance to work on a meaningful chunk of work that was polished enough, and tested enough, to be proud of.

Here are some things about Shape Up that our Engineering Manager, Andy Stanford-Bluntish, highlights as improvements from the old way we did things:

Scrum’s strict processes sometimes felt unnecessary in our small, casual team of less than 10 people.

Shape Up is way more flexible as a methodology, and we’ve been able to shape it (ha) into something that works for us. We’re all highly competent and experienced, so we appreciate that Shape Up discourages micromanaging while promoting discussion.

Features weren’t being shipped as quickly as we wanted.

Since we started using Shape Up, we’ve released the following projects to production:

- A significant revamp of our pricing model that involved rewriting a lot of logic and UI components

- Advanced Account Management, which introduces multiple levels of permissions for teams sharing a Flood account

- Free load testing and support for governmental organizations, including the state of New Jersey

- Optimizing our infrastructure so that we could contribute spare computing capacity to coronavirus research via BOINC

- Flood Agent, a new way to run floods on your own infrastructure (including on-premise deployments)

- Integration with Google Cloud Platform as one of the cloud providers you can run floods on

- SOC2 Type I Compliance to make our commitment to security official

- A new marketing site, developed in-house

- Release preview for Flood Insights, an all-new analytics engine with customizable dashboards

- A much-improved version of Element

Pretty good for a small team.

Conclusion

While we don’t think that any methodology is universally the best one for every team, we’re enjoying the advantages of Shape Up for the Flood team. We’ll continue to tweak elements of it to help us build a better Flood for all of you.