Performance testing the Dutch coronavirus hotline

Read the original Dutch version here. This English version was first posted here.

On June 1st, 2020, the National Institute of Health and Environment (RIVM) announced that everyone with certain symptoms could call the hotline 0800-1202 to arrange a free COVID-19 test. The promise: call today, get tested tomorrow, and receive the results the day after that. The reality, though, did not live up to expectations.

The opening day of the hotline was chaotic, and many Dutch people reported connection problems due to a system overload. Yet this could have been prevented with a better understanding of how human psychology can affect application performance.

The situation

According to Dr. Ann Vossen, chairperson of the task force charged with scaling up mass testing in the Netherlands, the country was ready to process 30,000 tests per day. This number corresponds to the national capacity of all the municipal health clinics (GGDs) in the Netherlands. Despite this claim, though, only 1,146 people were actually tested on the first day of testing (the day after the opening of the hotline). Perhaps more importantly, only 5,748 appointments were set on June 1st. The situation was no doubt exacerbated by the overwhelming 323,000 people who called the hotline on its first day, prompting even the telephone operators to admit that they’d had troubles logging into the appointment system.

Bron: From @ggdghornl, Twitter

Bron: From @ggdghornl, Twitter

[“We see that there are many calls going to 0800-1202. You can call for an appointment until 8pm tonight. Please try your call later to avoid long wait times.”]

On Twitter, users shared horror stories: one claimed to have waited on the line for 6 hours, only to be told that the system was down and no appointments could be made; another complained about getting disconnected after getting in touch with an operator. Yet another posted a video of calling the hotline and a recorded message saying “Al onze medewekers zijn op dit moment in gesprek. We zullen u zo snel mogelijk te woord staan. [All of our operators are currently on other calls. We will answer you as soon as possible].”

The second day was somewhat better: there were 11,000 appointments made, partly because of the lower amount of phone calls and partly because of some fixes of technical problems. In the first week, the number of appointments increased to 50,000 (about 7,142 per day), which was still significantly lower than expected.

There are some lessons that we can learn from this case study.

Source: Coronavirus test procedure from GGD Hollands Midden

Source: Coronavirus test procedure from GGD Hollands Midden

English translation:

Do you have these (mild) symptoms?:

- cough

- blocked or runny nose

- fever

- loss of smell or taste

Step 1: Make an appointment

- Call the national number 0800-1202

- Have your BSN with you when you call

- Make an appointment to get tested at one of our locations

Step 2: Test

- Go to the selected location at the scheduled time

- You will be tested at the test location

Step 3: Results and eventual start of source and contact research

- You will be called with your results within 48 hours

- If you are infected with the coronavirus, the GGD will call you for source and contact research *If you show more serious symptoms, or if you fall within a high-risk group, report to your doctor or to the emergency help line.

The effect of fear on performance

This coronavirus has already shown us a side of humanity that we’d perhaps rather not see: fights over toilet paper, chaos on the stock market due to panic, and sabotage of 5G cell towers based on a belief that they caused COVID-19. As much as we’d like to believe it, we’re not always the most rational beings. We all have the tendency to behave unpredictably, especially when we’re afraid.

It’s no wonder that the coronavirus testing line was so welcome. The fact that there were 323,000 callers on the first day is even more remarkable when we remember that majority of Dutch residents had been in self-isolation for months at that point, which lowered their chances of contracting the virus. In theory, the fear that drove these callers might have been somewhat irrational, but not unpredictable.

In English, we call this FOMO (Fear of Missing Out). We’ve already clearly seen how FOMO can drive users en masse to an application, with effects on its performance. In this case, people were afraid that coronavirus test shortages would mean there weren’t enough tests to go around, and they wanted to be first in line to get tested.

Another problem was that one in four callers just wanted general information about COVID-19, despite government pleas to keep the hotline free for coronavirus test appointments only. It didn’t help that the hotline opened on a Dutch national holiday, White Monday, and more people were home than usual for a Monday. The high number of unrelated calls was unexpected, but nevertheless factored into system overload.

What could we have done to improve this system?

Improvements to the corona hotline

Better estimation

As difficult as it is to predict FOMO’s effects, we can still try. We can make educated guesses based on related statistics.

Just one month before the coronavirus test hotline was opened, Jaap van Dissel, the head of RIVM, estimated that there were up to 700,000 Dutch residents infected by the coronavirus. Why, then, was it such a surprise that more than 300,000 of them had called? Furthermore, the RIVM had encouraged people with a broad list of symptoms (such as colds, coughs, or fever) to call, and it’s reasonable to assume that some people with conditions other than COVID-19 might also have called.

Even if we assume that 20% of the 700,000 people with the novel coronavirus did not have symptoms (according to WHO research), we still arrive at a predicted 140,000 calls, which is still 25 times what was the coronavirus testing system was able to process on the first day.

If we have an educated estimate, we can start testing.

Injecting load

When a resident calls the hotline, the call is routed to one of several operators working from home. This is often done with a telephony server that forwards calls based on some type of round-robin system. We can execute load tests on this server to determine how many phone calls a server can process and route successfully, with minimal delay and without message queueing.

Then, the operator enters personal information from the caller into the appointment system, including their government identification number (BSN) and address. We can surmise that the system checks the identity to verify the validity of the BSN, and then sends some details to a database. The closest municipal clinic to the caller can then use the data to process and schedule an appointment. We can also inject load at this stage by simulating the calls that the appointment system creates with an API load testing tool like JMeter or Gatling.

Using different test scenarios

With such a public announcement of the hotline’s opening, a spike test before release could have yielded some useful information. In a spike test, we simulate a sharp increase in users over a short period of time. For example, we could have simulated an increase in users from 0 to 700,000 on the telephony system over 10 minutes to see how the application would have handled that.

Soak tests could also have been useful in this case. The hotline’s opening hours were from 8 am to 8 pm, so it was open for 12 hours in total. With soak tests, we can generate load on an application for an extended amount of time. Soak tests can reveal memory leaks or other bottlenecks in the processing of data that might occur after hours.

These are ways we could have tested the system as it is, but are there improvements that we could have made in the system to make it more resilient to reduce the FOMO factor?

Using automation to lessen FOMO risk

The system had some manual parts of the process that may have exacerbated load issues. Here’s how this system could have been automated to reduce bottlenecks.

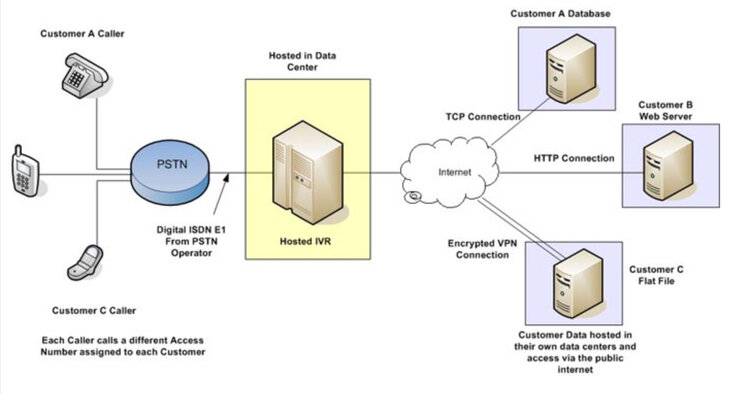

Interactive Voice Response

Telephony servers commonly use Interactive Voice Response (IVR), an automated menu system for voice calls that uses either voice recognition or keypress tones to navigate a user through a series of choices. We’re all familiar with it: “For Dutch, press 1. For English, press 2…” Such a system might have helped reduce the overall load by quickly filtering out callers in the 25% who weren’t interested in creating an appointment. “If you’d like to book an appointment for a coronavirus test, press 1. Otherwise, please call the information hotline at….”

Here’s what an IVR system could look like:

From: Vanguard Networks

Load testing IVR systems can be difficult, and it usually requires the use of highly specialized commercial tools. However, introducing a new tool may also increase the time required for load testing.

From: Vanguard Networks

Load testing IVR systems can be difficult, and it usually requires the use of highly specialized commercial tools. However, introducing a new tool may also increase the time required for load testing.

Building a web app

Another approach would be to implement a web app to verify identity and capture personal information quickly. In the Netherlands, we already have DigiD, an identity verification system that is heavily used for governmental services. Mijn Overheid, which is a central government portal accessible to every Dutch resident, already interfaces with DigiD as the sole method of logging in. Reusing these existing services could have saved a lot of the work on a web app— not to mention reducing the bottlenecks inherent in a more manual process like a telephone hotline.

Source: Mijn Overheid

Source: Mijn Overheid

Testing the system end-to-end

We’ve identified a few ways to load test various components of the coronavirus hotline, both in its current incarnation as well as in hypothetical improved versions. Isolating each component and running load tests at that level can help us resolve performance issues inherent in the component. However, there are still bottlenecks that are only revealed when the integrations between components is tested as well. That’s where end-to-end testing comes in.

For the coronavirus hotline, end-to-end testing means being able to run load tests on the entire process and seeing how data flows from one to the other: the call forwarding from the telephony server, the identity verification system, the appointment system, the database of personal information, the servers of every municipal clinic, and the email/text notifications with appointment details. As modern applications grow more complex, it can be tempting not to run end-to-end tests, but we do so at great risk of functional or nonfunctional issues.

An area of end-to-end testing that is often overlooked is the human factor, which can also be a bottleneck. Had hotline operators been trained to ask early on in the call whether the caller wanted to make an appointment, to filter out unrelated calls? Can the coronavirus testing and test result processing, heavily involving manual work from medical professionals, match the stated requirements (test within 24 hours, result within 48 hours) even when the digital components are performant? Some people waited for an hour in the cities of Eindhoven and Goes due to traffic congestion from cars near the test centers, leading to delays in the testing schedule.

While it can be difficult to load test these logistical systems with automated tools, they may have significant effects on the overall performance of an application and should be considered.

Conclusion

Often, performance issues can lead to a tangible loss in profits or a more intangible loss in reputation. In this case study, poor performance had a direct impact on people’s health. Potentially sick people were unable to make appointments to get tested, and later treated. Delayed tests could have led to an increased infection rate as people waited for a confirmed diagnosis. Hotline operators also admitted that slowness in the system led to them sometimes giving out test results against instructions to wait for trained medical professionals to do so.

Human psychological factors can make a system more complex to load test. According to Andrea Evers (LUCM), a health psychological professor, “Door de uitbraak van corona zijn mensen in een langdurige stresssituatie beland. Onzekerheid, onvoorspelbaarheid en oncontroleerbaarheid maken dat ze de behoefte hebben om zaken juist wel te controleren of voorspelbaar te maken [The coronavirus outbreak has put people in a situation of chronic stress. The uncertainty, unpredictability, and helplessness of the situation cause a need to make things controllable or predictable].”

As performance testers, we can use statistics and a systematic attitude combined with knowledge of human factors in applications to try to predict the unpredictable.