FOMO and performance testing: Why Robinhood went down

Originally posted here.

Angry customers flocked to the internet when the Robinhood investment brokerage app went down last Monday and part of Tuesday, leaving them unable to trade stocks on a day where Wall Street reported historic gains. Could this have been prevented?

The answer is yes. Applications should always be assessed for risk and tested accordingly. Risk-based load testing helps unearth problems that would otherwise only surface in production. Testing applications end-to-end as a system instead of just as a collection of isolated components allows us to build software that is more resilient. The problem is that this type of testing can be difficult to carry out. In this article, I’ll go through the entire process.

What is Robinhood?

Robinhood is an app I’ve personally had my eye on since it opened a waiting list about five years ago for Australians wanting to see the American company come to our shores. It doesn’t look like it’s happening now, but if that waiting list still exists, I’m on it.

Robinhood is a brokerage app that takes inspiration from the legend it was named after to “give to the poor,” bring zero-commission trading to its customers. Instead of earning from commissions, Robinhood makes its money from a variety of other methods, including premium platform fees, interest on customers’ uninvested capital, and payments received in exchange for coursing customers’ orders through third-party market-makers. It’s an enticing premise, and one that the company has used in conjunction with mobile apps to appeal to millennials and technophiles.

Source: From Robinhood’s homepage

What caused the Robinhood app to fail?

Unfortunately, its wild success with the tech-savvy crowd also meant that when it went down last Monday morning in the US, its customers took to the internet in droves to draw attention to the failure. In a blog post from Robinhood, the company’s co-founders, Baiju Bhatt and Vladimir Tenev, admitted that the outage was due to “stress on [their] infrastructure— which struggled with unprecedented load.”

The outages you have experienced over the last two days are not acceptable and we want to share an update on the current situation. Our team has spent the last two days evaluating and addressing this issue. We worked as quickly as possible to restore service, but it took us a while. Too long. - Baiju Bhatt and Bladimir Tenev

Bhatt and Tenev went on to explain that the load on their servers had caused a “thundering herd” effect. This effect describes a situation in which a backend server receives a large number of concurrent requests and, instead of different threads processing these requests simultaneously, all threads attempt to process the same request.

If you’ve ever played four-player Overcooked, it’s like having everyone sprint to a fire extinguisher to try to put out a fire from overcooked pasta, but instead, the constant button mashing means you just pass the extinguisher around and yell at each other while the fire rages on. Before you know it, the entire kitchen is on fire.

Source: From Twitter user @csac0425

So the technical cause of the outage was an infrastructure problem.

But I think the REAL cause was FOMO.

What is FOMO?

FOMO is the Fear Of Missing Out, and it’s a phenomenon that’s been particularly exacerbated by social media. Instead of only hearing news from people you interact with in the physical world, it just takes a few seconds to open up Twitter on your smartphone and see what thousands of people are talking about. Twitter will even helpfully tell you what’s “trending” in your country, and other social networks also employ algorithms to determine what messages to show you.

How does FOMO affect application performance?

We can see FOMO in how people have reacted to the coronavirus COVID-19. Despite pleas to leave masks for medical professionals at real risk, people have bought out the stock for these masks despite living in countries with little to no sign of the coronavirus. In Sydney, Australia, residents are stockpiling toilet paper (of all things) in large quantities, clearing out shelves from supermarkets, and getting into knife fights over toilet paper due to their panic at the thought of doing without.

This photo of an empty toilet paper aisle was taken by our Principal Engineer, Lachie Cox, in a supermarket in Sydney last week. FOMO of this magnitude ultimately also manifests itself in the stock market. The Dow Jones Industrial Average, which represents the performance of the top 30 largest companies in the US, dropped by 3,500 points last week amidst fears that the coronavirus would stall production in countries most affected by COVID-19, leading to lower returns across the board.

Then, an abrupt about-face. The Dow went from recording its biggest ever loss in a single day on Thursday to posting a record gain of 1,200 points on Monday.

Guess who gets to adjust to all this volatility.

Robinhood’s founders reported that the “highly volatile and historic market conditions; record volume; and record sign-ups” contributed to the infrastructure issues they faced. We can only imagine just how many users they saw on their systems during this period.

FOMO creates mass hysteria and panic, both of which cause customers to behave irrationally and likely very differently than previously recorded. So how do you create a workload model that accounts for this volatility? How do you tailor your load tests for FOMO? I’ll run you through the process, using Robinhood as an example.

Does your application require FOMO load testing?

All testing should be risk-based. Start with why: why should you test an application component? Why does your application require this kind of testing or that one?

In Robinhood’s case, there were a few indicators that pointed to the necessity of FOMO testing:

-

A customer base made up of a younger, tech-savvy generation. This demographic is very likely to take to social media with complaints, making negative publicity a real risk.

-

Complexity. Robinhood’s systems must receive customers’ orders, forward and place those orders to market makers, and display real-time market data. Robinhood customers can also purchase options on stocks as well as cryptocurrency, further increasing the complexity.

-

Financial component. Anything that involves taking people’s money should have a high priority for any testing.

When it comes to your money, we know how important it is for you to have answers. - Baiju Bhatt and Bladimir Tenev, co-founders of Robinhood

-

Record-breaking growth. Robinhood had 1 million users in 2016, 6 million in 2018, and 10 million last December, according to CNBC. Exponential growth brings some major growing pains.

-

Industry history of expensive failures. Quartz points out that software or infrastructure failures have cost the financial industry millions in recent years.

-

Recent legal action. The regulatory body FINRA fined Robinhood US$1.25 million just last December for placing orders for customers without looking for the lowest price. While this isn’t a huge fine for a company that was valued at US$7.6 billion last July, any legal action should make a company tread more carefully.

These are solid reasons to warrant load testing Robinhood’s systems beyond just “expected” load.

Planning for FOMO

Once you’ve determined that your application is susceptible to FOMO, the next thing to do is plan how to structure your load tests to include its effect in your test runs.

What type of app is it?

Robinhood consists of three apps: two for mobile (iOS and Android) and one for the web. It is currently only available to US residents, which means that getting mobile apps downloaded is problematic as it would entail changing countries in the app stores to get access. Since I live in the Netherlands and I don’t want to do that, I’ll focus on the web app specifically when scripting the load test, and I’ll assume that the same underlying application servers service both web and mobile apps.

Workload modeling

Business processes to test

Given that the app went down on a day where markets were up, we can assume that most of the people on Robinhood’s apps were doing one of two things:

-

Signing up

-

Buying shares

We should ideally test both, but let’s focus on signups here because it’s easier to test without access to the actual app (which requires a US social security number).

Number of virtual users at peak load

Let’s try to come up with a number of users that we can use as Robinhood’s peak hourly load. This task would be easier if Robinhood shared their analytics, but we can still make some educated guesses with what has been made public.

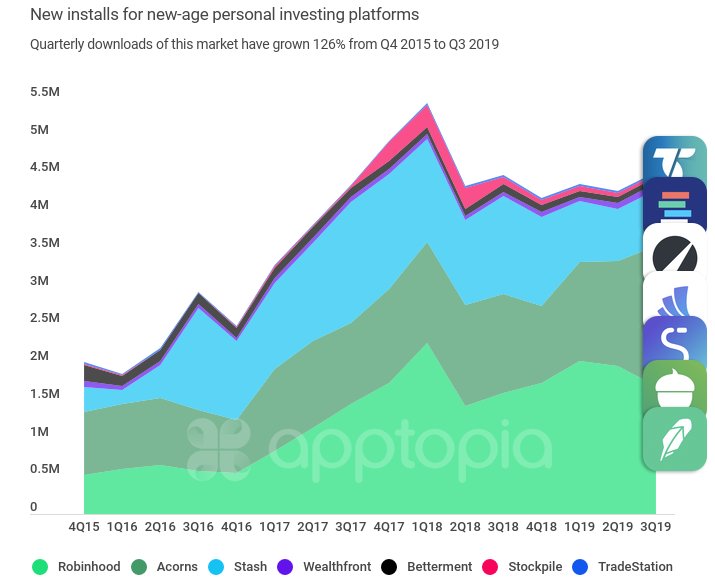

Source: Image from Apptopia

According to Apptopia, Robinhood’s highest number of mobile installations was in 2018, when it saw 2 million downloads of its mobile app in a quarter. This period coincides with when Robinhood released cryptocurrency trading support, which looks like increased signups—in the third quarter of 2019, this figure was about 1.5 million. 2 million quarterly downloads translates to about 666,666 downloads per month. Let’s call that 700,000 and take this number of mobile downloads as a starting figure.

The stock market is only open on the weekdays, so we can divide 700,000 signups a month by 20 days, and we get 35,000 signups a day. The markets are also only open for about 7 hours a day, but the load probably isn’t evenly spread out across the 7 hours— I would expect that people would have more time during lunch to sign up for Robinhood. So let’s say that the majority of those signups would happen within three hours (from 11 am to 2 pm, for example). By dividing 35,000 signups per day by 3 hours, we get about 11,667 users per hour. Let’s round that up to 12,000.

How do we translate this to the number of virtual users we need to run? Let’s think about how long each user stays on the app. The signup process does require approval, so that’s a hard stop— new users won’t be able to sign up and then start trading immediately afterwards. This approval could take up to a day, or up to seven days if documents are required.

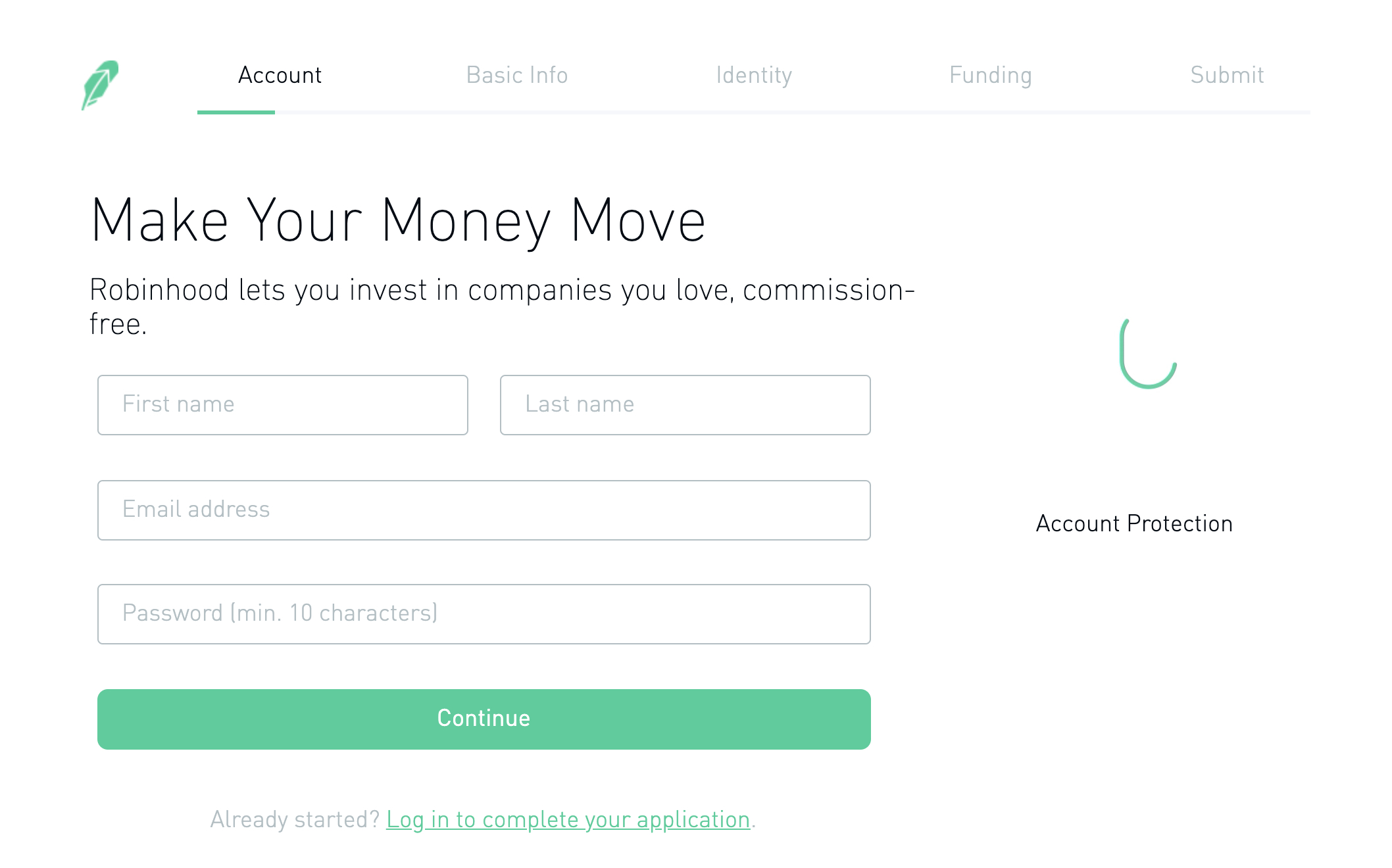

Looking at the application form itself, we can see it is relatively standard and requires only information that most people are likely to have handy (social security number and contact details). I timed how long it took me to go through the part of it I could access, and I estimated that 10 minutes would be sufficient time to go through all the tabs.

Source: Robinhood

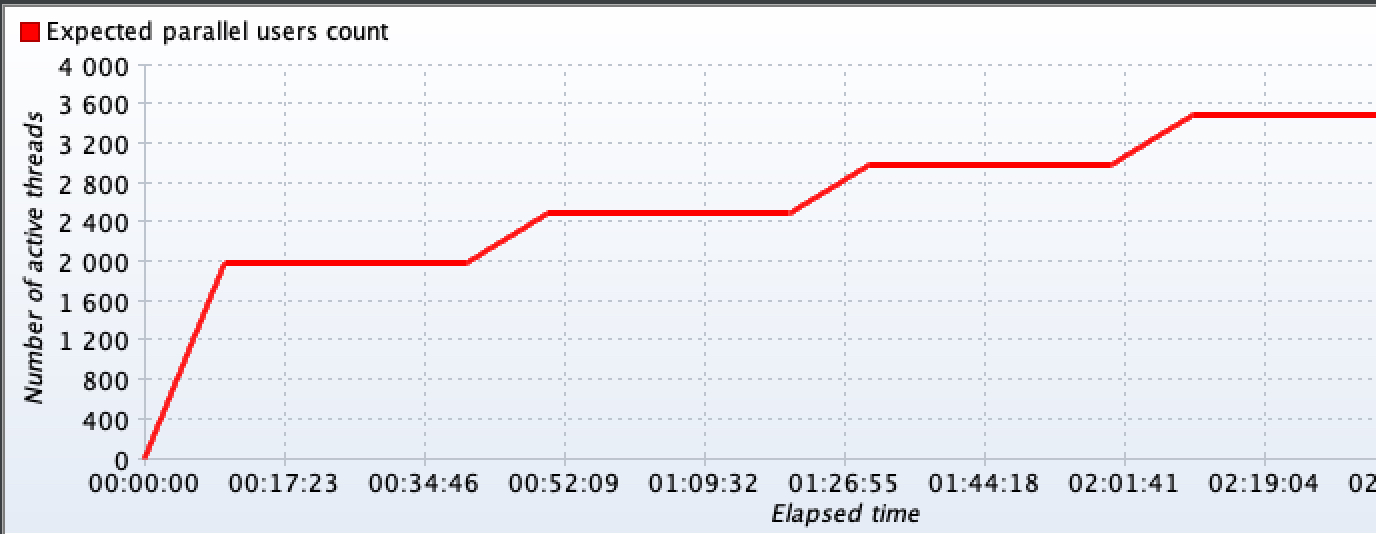

We want to spread out users evenly across the hour— that is, we don’t want 12,000 users to sign up and leave, all within 10 minutes. We want equal portions of those users to be signing up throughout the entire hour. Dividing 12,000 by 6 (the number of 10-minute intervals in an hour), we get 2,000. 2,000 is the number of threads we need active at any one point of time. Each of those threads signs up one user for 10 minutes, then signs up 5 more users until the hour is up.

So we have our figure: we need 2,000 virtual users per hour to simulate 12,000 signups in an hour.

Test scenarios

In addition to running the standard battery of load tests, testing for FOMO requires exploring the upper limits of the application. Assuming the peak load testing goes well, we can use the 2,000 virtual users per hour figure from our peak load calculations as a starting point for these more destructive tests. To this end, here are some test scenarios I’d consider running if I were testing the Robinhood app:

-

Soak testing. Soak testing means running typically a little less than the peak load profile, but over a longer amount of time. In Robinhood’s case, perhaps we could run 1,000 virtual users for 8 hours. We would expect that the response times reported during this test would be the same; otherwise, there is likely a performance bottleneck, such as a memory leak.

-

Stress testing. Stress testing means increasing the number of users on an application at regular increments until the application crashes. We can start with 2,000 virtual users per hour, and then add 500 users every 30 minutes to see how the application handles it. This test helps determine how much room there is for growth.

Source: Stepped load profile for stress testing, generated in JMeter

- Resilience testing. Resilience testing involves running the peak load test and then simulating an outage by turning off key components to see how the application behaves. If two servers share the load, for instance, we could turn one off and check to make sure that the user sessions on the terminated node are moved over onto the remaining node. This test shows whether the application recovers gracefully from an unforeseen event.

All these tests help us prepare for the unexpected, and they might have identified the “thundering herd” problem that contributed to Robinhood’s outage.

Scripting for FOMO

Tool selection

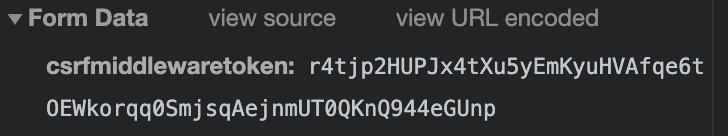

To test mobile as well as web apps, I would typically use a protocol-level load testing tool like JMeter to simulate the load. However, I’ve already done that. I also noticed that Robinhood makes use of some dynamic parameters, such as a csrf token:

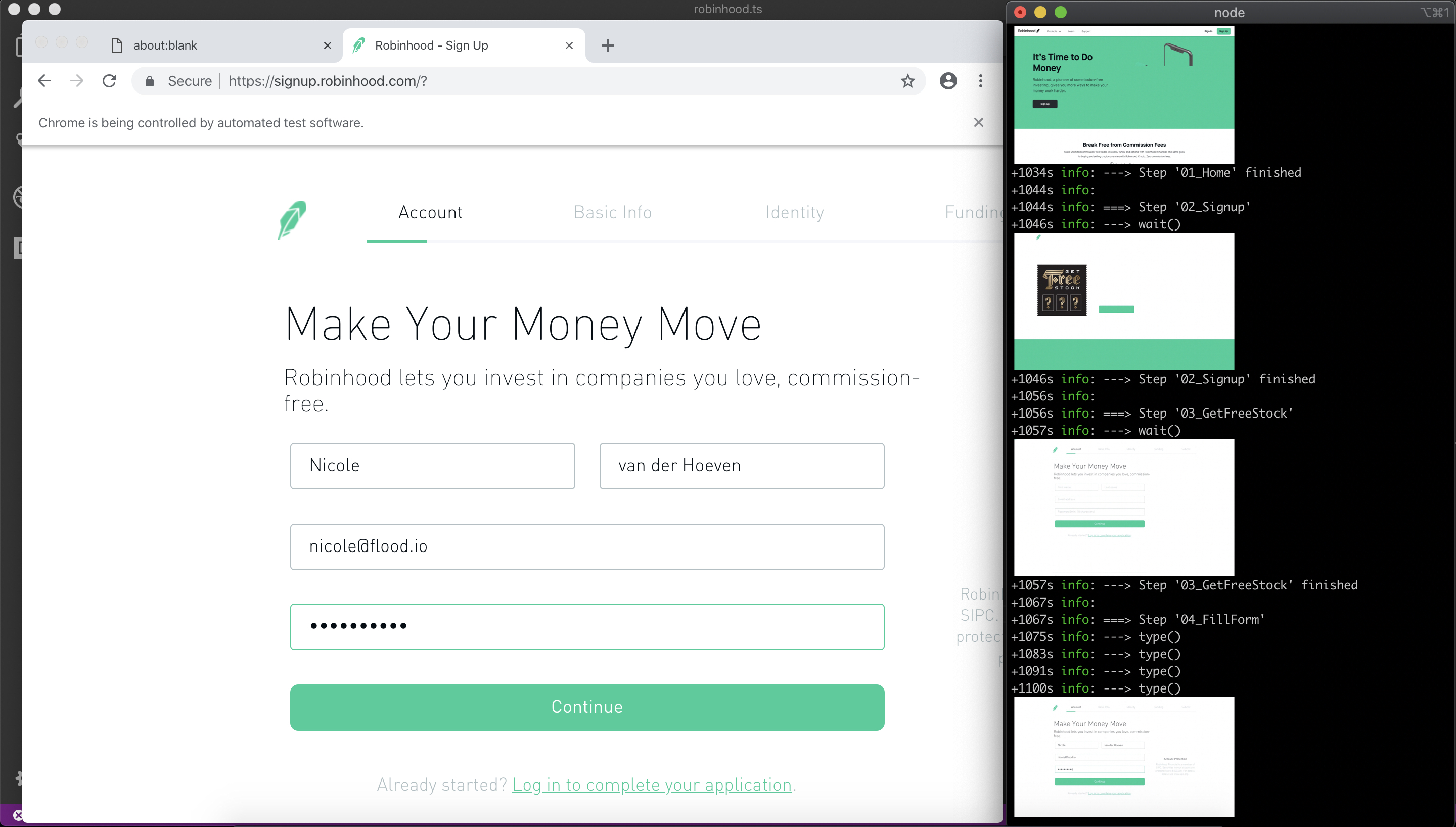

Source: Chrome Developer Tools on Robinhood We can usually find the value of this token in the response of the previous page. It is a security feature to allow Robinhood to verify that the same users make all requests in the same session. Tokens can be scripted around in a tool like JMeter, but it can be time-consuming. So for this article, I decided to show another tool that makes this problem go away. I used Flood Element, which is an open-source tool we created based on Puppeteer. One of its advantages is that it runs on the browser level. Instead of diving into HTTP requests and tokens, I just told Element which buttons to click.

I wanted a script that would do the following things:

-

Navigate to Robinhood’s home page.

-

Click on “Sign Up”.

-

Click on the “Get Your Free Stock” button.

-

Fill out the signup form.

Note that I stopped short of actually submitting the form because I don’t want to create dummy accounts on Robinhood’s database— I just want to show how this flow can be scripted with Element.

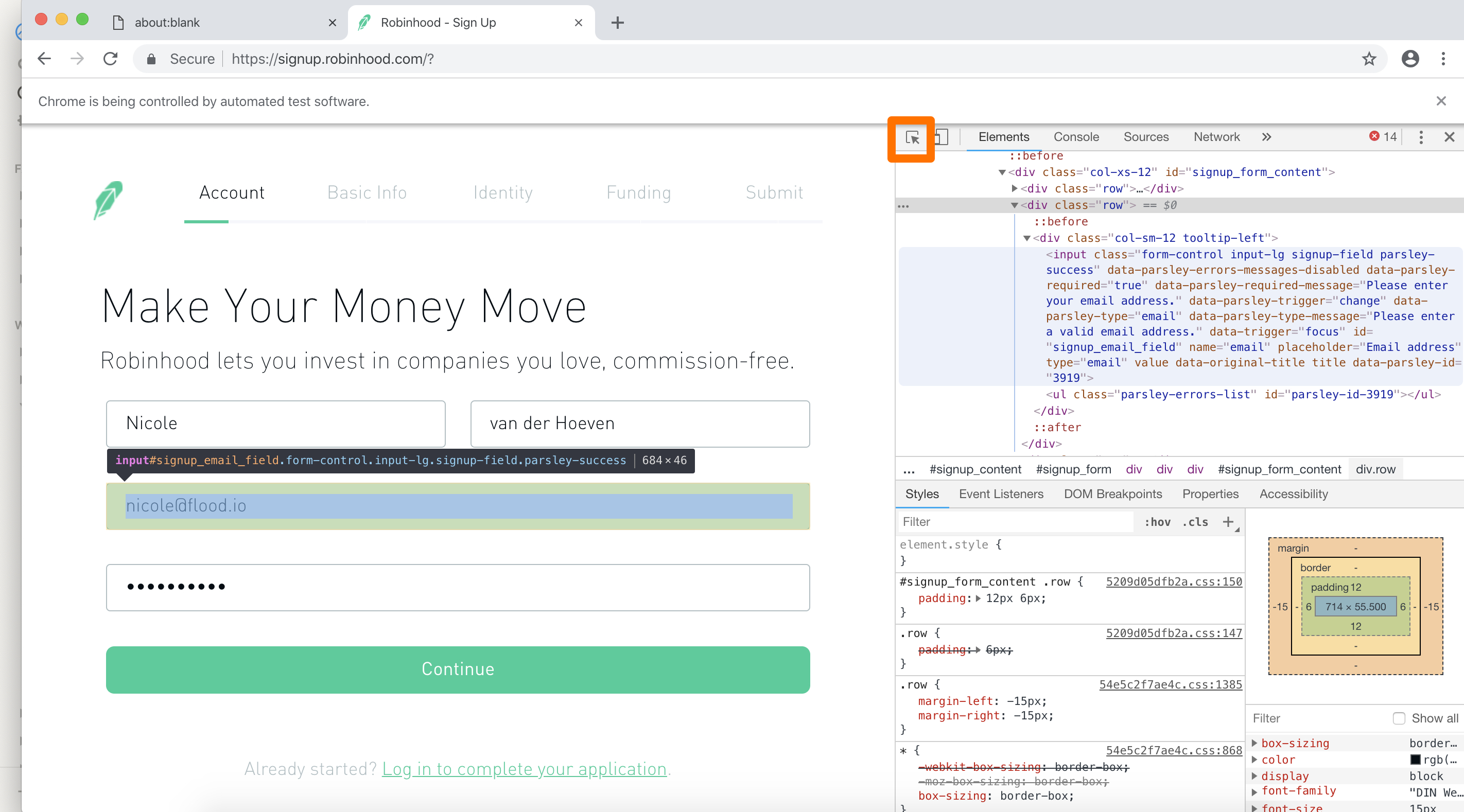

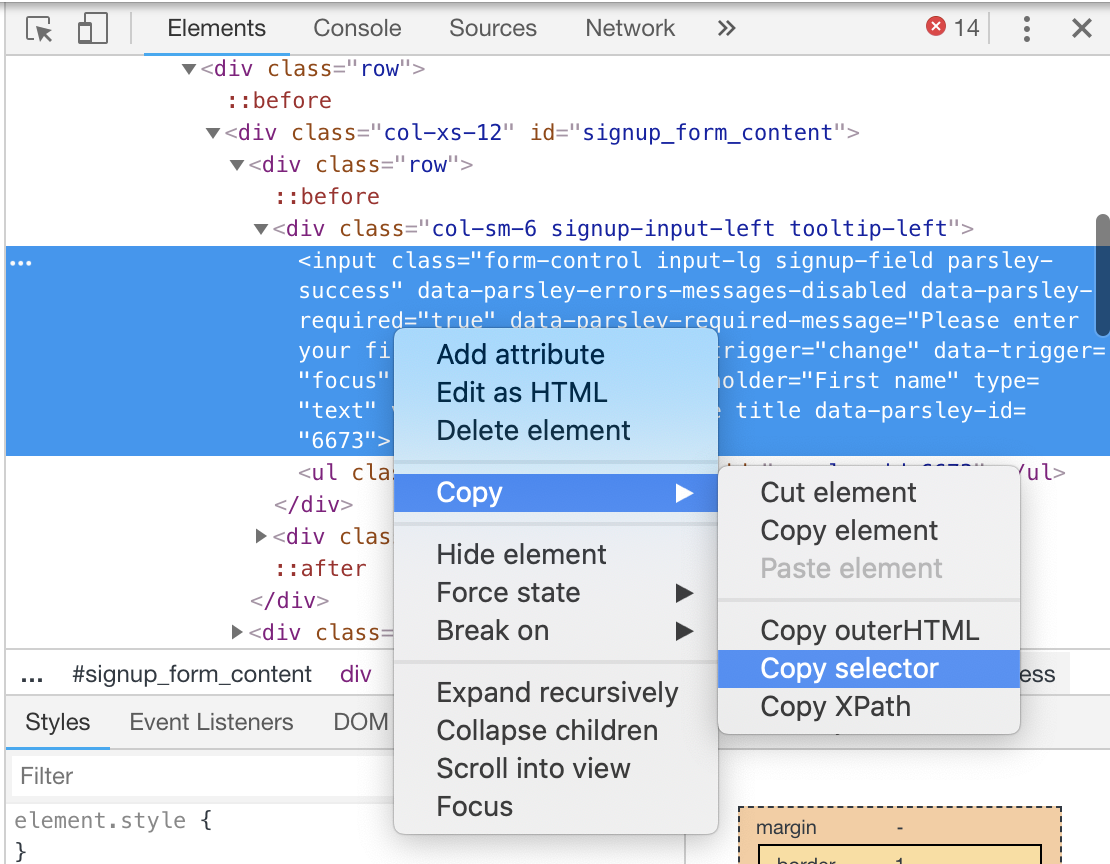

To help me identify the elements on the page that I wanted the script to interact with, I used Chrome’s built-in Developer Tools. Specifically, I used the Inspect Element button (in orange below) to click on a field and find where it was in the code.

For instance, to find out how to identify the email field, I right-clicked on the code on the right, hovered over Copy, and then clicked Copy selector.

This gave me the value #signup_email_field, which I then used in the script like this:

//Type Email address

await browser.type(By.id('signup_email_field'),'nicole@flood.io')

Here’s the script that I ended up with:

import { step, TestSettings, Until, By, MouseButtons, Device, Driver, ENV } from '@flood/element'

import * as assert from 'assert'

export const settings: TestSettings = {

loopCount: -1,

clearCache: true,

disableCache: true,

actionDelay: 8,

stepDelay: 10,

screenshotOnFailure: true,

userAgent: 'flood-element-test',

}

export default () => {

step('01_Home', async browser => {

//Navigate to Robinhood homepage

await browser.visit('<https://robinhood.com>')

//Validate text

let validation = By.visibleText('It’s Time to Do Money')

await browser.wait(Until.elementIsVisible(validation))

await browser.takeScreenshot()

})

step('02_Signup', async browser => {

//Click "Sign Up"

let signupBtn = await browser.findElement(By.xpath('//a[@href="<https://signup.robinhood.com>"]'))

await signupBtn.click()

//Validate text

let validation = By.visibleText('Free Stock Waiting For You')

await browser.wait(Until.elementIsVisible(validation))

await browser.takeScreenshot()

})

step('03_GetFreeStock', async browser => {

//Click Get Your Free Stock

let freestockBtn = await browser.findElement(By.xpath('//a[@href="<https://signup.robinhood.com/?">]'))

await freestockBtn.click()

//Validate text

let validation = By.visibleText('Make Your Money Move')

await browser.wait(Until.elementIsVisible(validation))

await browser.takeScreenshot()

})

step('04_FillForm', async browser => {

//Type First name

await browser.type(By.xpath('//input[@name="first_name"]'),'Nicole')

//Type Last name

await browser.type(By.xpath('//input[@name="last_name"]'),'van der Hoeven')

//Type Email address

await browser.type(By.id('signup_email_field'),'nicole@flood.io')

//Type password

await browser.type(By.xpath('//input[@name="password"]'),'demo123456')

await browser.takeScreenshot()

})

}

In every step, I also added a takeScreenshot() , which is one of my very favorite features of Element. It’s so useful to be able to save these screenshots and use them to determine exactly what’s happening in the script. Here’s what it looks like running my Element script locally. The automated browser is on the left, and my terminal (iTerm) is on the right, running Element.

Running a FOMO test

Now we’ve got a script that runs locally. How do we run it at scale? Additionally, Robinhood won’t allow users outside the US to sign up. How do we make sure that our virtual users are allowed to sign up?

The answer is a load testing platform like Flood.

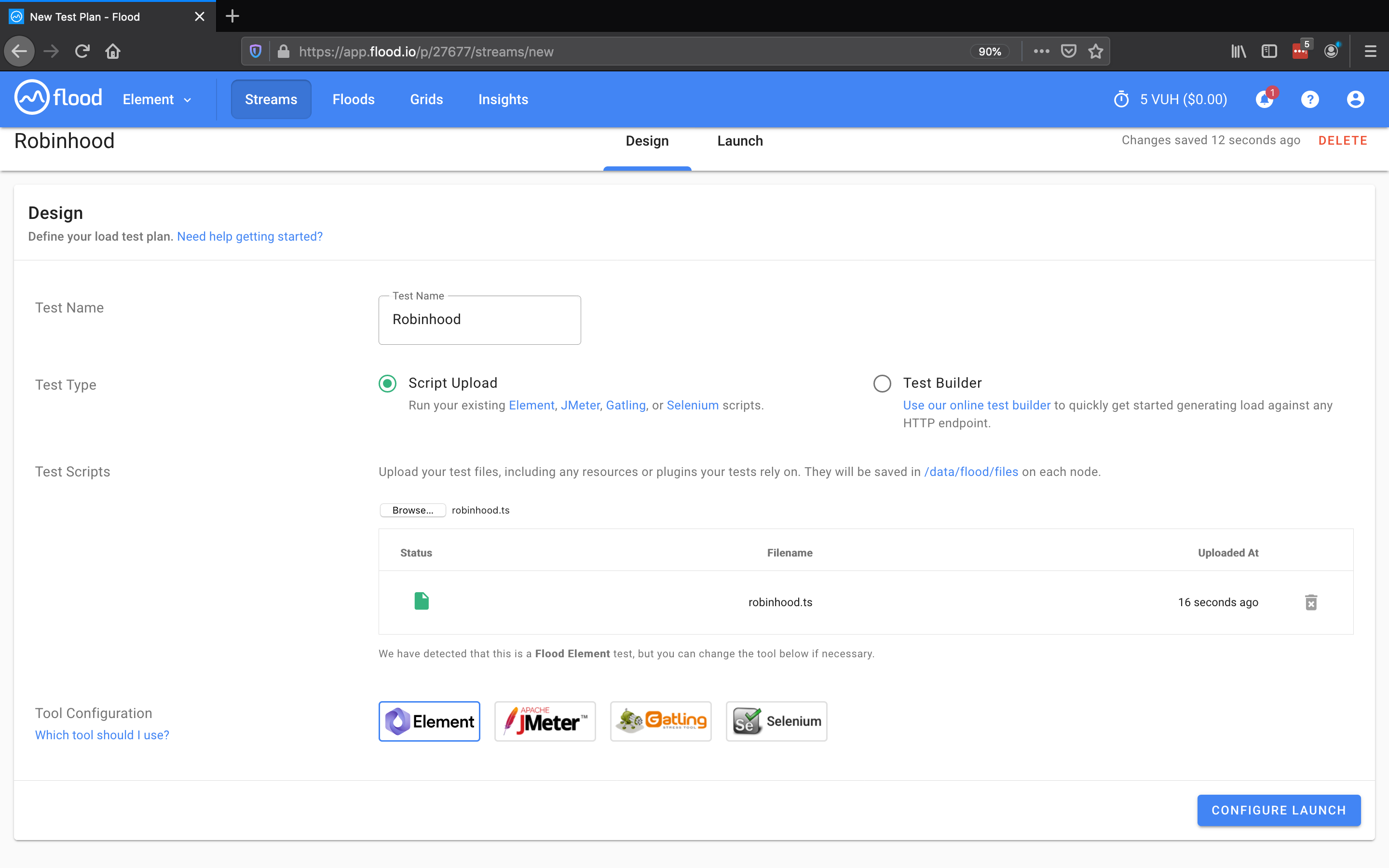

With Flood, running our script is a matter of uploading the script and selecting some options.

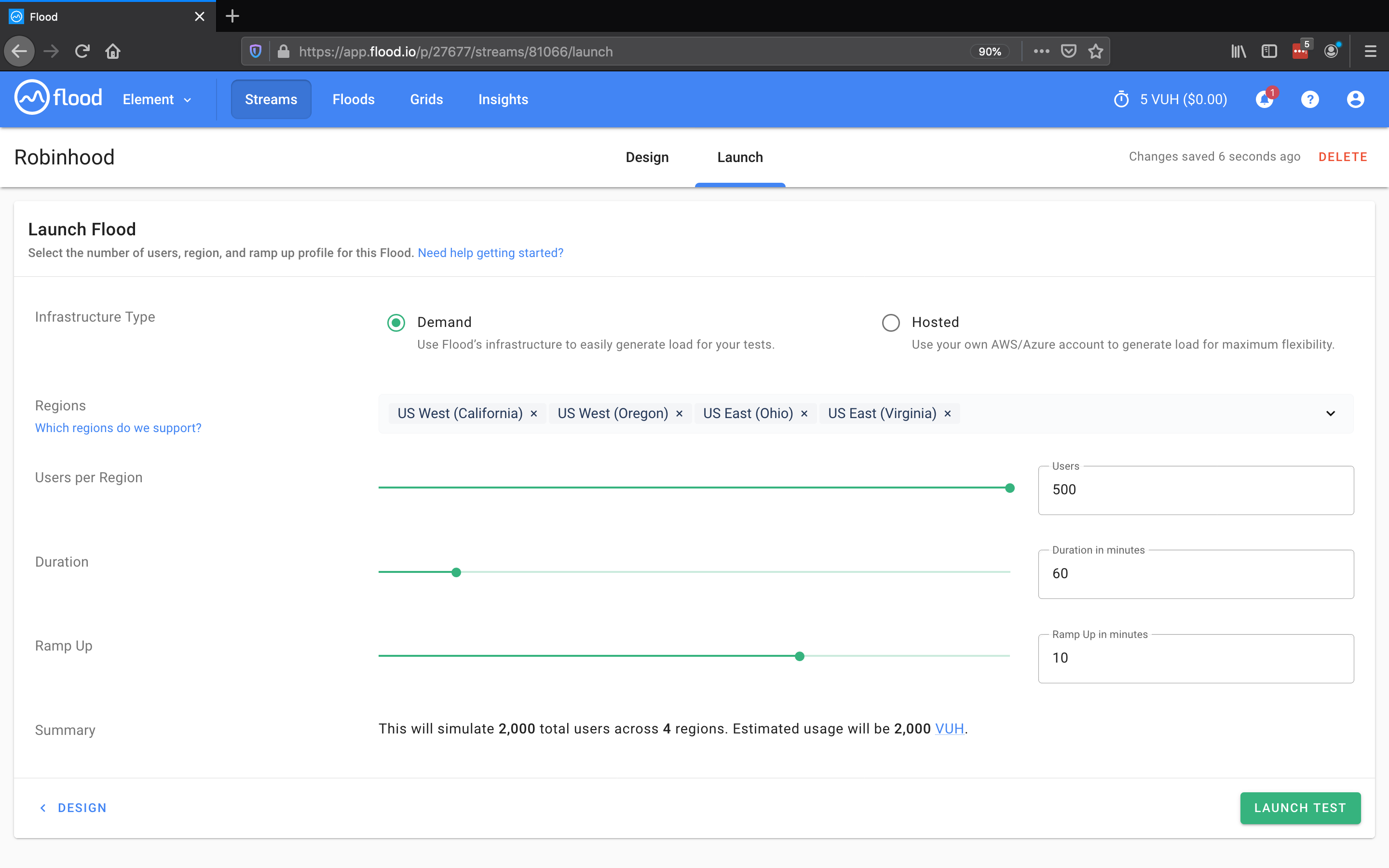

The Flood test design interface Flood also lets us choose which regions to generate load from. Below I’ve got it set up to run for an hour from four different US cities, with each one starting 500 users. This configuration gives us our 2,000 virtual user figure.

If this peak load test goes well, we could then go on to run the other test scenarios that we described earlier. Each one puts pressure on application servers in different ways, identifying performance bottlenecks.

Results and reruns

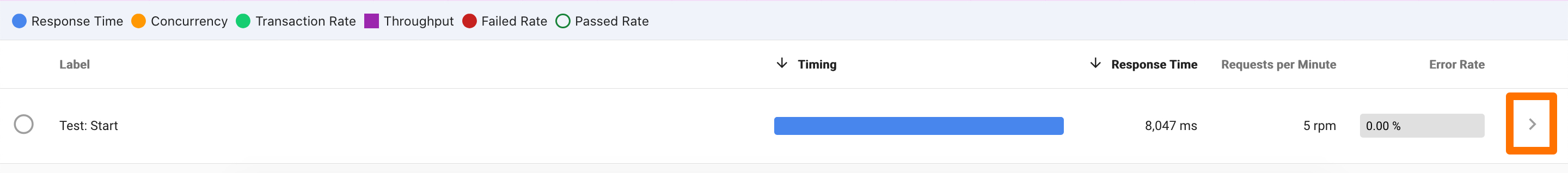

Since Robinhood is a live application, I didn’t run the test— it’s never a good idea to load test a domain you don’t own when you’re talking about thousands of users. However, here’s a shareable link to another small Element test I ran previously.

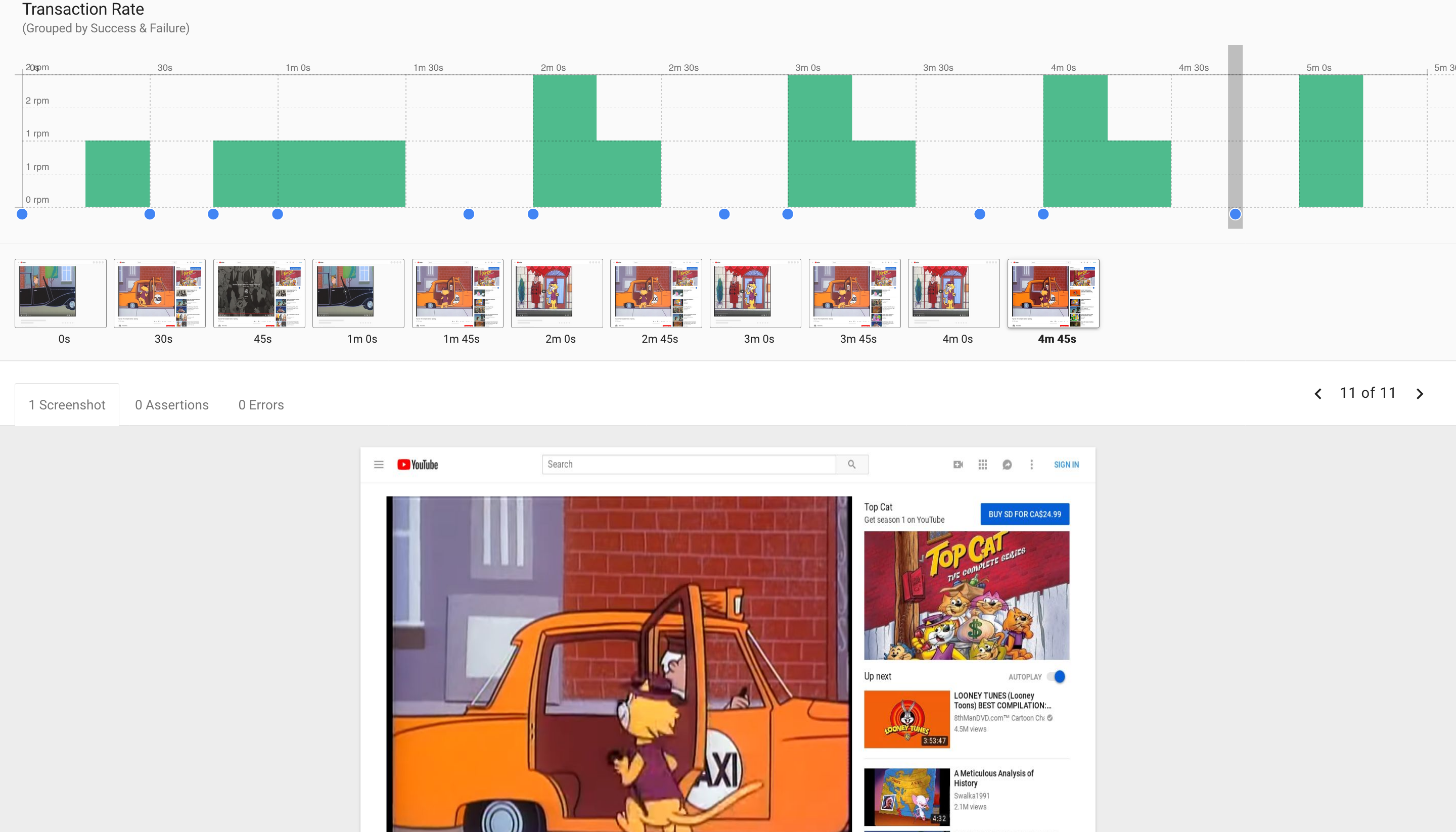

Real-time dashboards like that one on Flood allow you to get a quick look into how the load test is running and to make any changes if necessary. When testing for FOMO, I think they’re invaluable. For example, during a stress test where users are added at regular intervals, a real-time dashboard would help you identify increases in response time as a result of the increased number of users. It would also let you monitor the test and stop it when necessary.

From the link above, click on the right arrow on the lone transaction.

That will take you to the Transaction Detail page. Remember those screenshots from Element? If you have any in your script, you’ll see them here, arranged according to time.

This lets you troubleshoot issues during FOMO testing and react quickly.

Conclusion

Even with sound load testing strategies in place, it’s challenging to plan for the massive spike in traffic that FOMO can bring, yet it’s necessary to do so. FOMO, as a phenomenon, is only going to increase in magnitude as social networks make it easier to spread fear, uncertainty, and doubt as well as information.

We may not be able to determine precisely what will break, or when, but what we can do is put systems into place to plan for it. We can assess an application’s susceptibility to FOMO and plan for end-to-end performance engineering of the system as a whole. We can start with the assumption that applications will fail and then determine the most likely candidates for that failure. We can routinely expose systems to traffic and circumstances that are extraordinary, and in doing so, we can improve our preparedness for something like FOMO.

FOMO is irrational and unpredictable— but that doesn’t mean it needs to be unexpected.